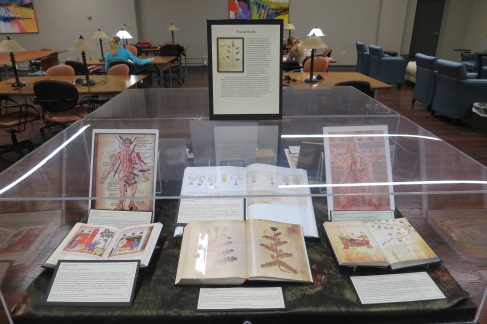

My interest in medieval demons began with my research for an entry in the Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters. I have been interested in monsters in general for a long time now, such as Beowulf’s Grendel and the draugar of Icelandic sagas, but it was a fascinating experience to focus specifically on demons, creatures that I define as fallen angels and malign supernatural beings of a nature intermediate between gods and men. In the early stages of this process I began to think more critically about what exactly a medieval demon is, and the wisdom of those who are more knowledgeable than I was a big help. For instance, in an email Peter Dendle pushed me away from simply classifying kinds of demons and towards thinking about different manifestations of “the demonic” in the medieval world, what he calls “a more nebulous, porous, [and fluid] conceptualization of a force, diffuse agency, or set of active principles, that may take on specific forms but is not necessarily bound by those forms.” Therefore, my revised understanding of “the demonic” refers to fallen angels, of course, but can also include elements of the natural world (storms, floods, and crop failure), harmful animals (whales and wolves), and even humans (invading armies, heretics, Jews, and Ethiopians). Along similar lines, Dendle mentioned how some prayers in the medieval liturgy use the same terminology for casting out demons and fighting storms, and some medical literature conflates demons (or demonic agencies) with elves, poisons, and worms, and considers these the cause of a wide range of physiologic dysfunctions.

My interest in medieval demons began with my research for an entry in the Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters. I have been interested in monsters in general for a long time now, such as Beowulf’s Grendel and the draugar of Icelandic sagas, but it was a fascinating experience to focus specifically on demons, creatures that I define as fallen angels and malign supernatural beings of a nature intermediate between gods and men. In the early stages of this process I began to think more critically about what exactly a medieval demon is, and the wisdom of those who are more knowledgeable than I was a big help. For instance, in an email Peter Dendle pushed me away from simply classifying kinds of demons and towards thinking about different manifestations of “the demonic” in the medieval world, what he calls “a more nebulous, porous, [and fluid] conceptualization of a force, diffuse agency, or set of active principles, that may take on specific forms but is not necessarily bound by those forms.” Therefore, my revised understanding of “the demonic” refers to fallen angels, of course, but can also include elements of the natural world (storms, floods, and crop failure), harmful animals (whales and wolves), and even humans (invading armies, heretics, Jews, and Ethiopians). Along similar lines, Dendle mentioned how some prayers in the medieval liturgy use the same terminology for casting out demons and fighting storms, and some medical literature conflates demons (or demonic agencies) with elves, poisons, and worms, and considers these the cause of a wide range of physiologic dysfunctions.

After completing my research and my encyclopedia entry, I have come up with a working thesis that tries to account for many manifestations of the demonic in medieval European texts. I claim here (and possibly in a future published project) that medieval conceptions of the demonic evolve over the centuries, from an anonymous demonic plurality in earlier texts (e.g. Anglo-Saxon poetry) towards individually classified, named, and acting demons in later texts (e.g. the writings of Caesarius of Heisterbach, Thomas Aquinas, and Dante). These later medieval literary and philosophical texts describe the activities of individual demons and seek to classify demonic nature. Furthermore, the precise definition of “demon” and “the demonic” expands in the later medieval centuries to include not only fallen angels but also evil spirits in general, especially as we transition into the Early Modern World.

Question 1: Do you have any initial objections or points of clarification for my thesis? In addition to the examples that I list below, what other early or later medieval texts, art, or other sources would you add to this discussion that fit into my thesis, complicate it, or even contradict it? (For instance, my fellow Woode-walkers brought Anselm and Augustine into the conversation and added a great deal to my understanding of demons in medieval theological thought, specifically their ordering among moral and immortal beings and their possible intercessory nature.)

Early Medieval Demonic Plurality

Peter Dendle describes anonymous and plural demonic nature in Satan Unbound: The Devil in Old English Narrative Literature. This manifestation can be found in texts like St. Boniface’s letter of 746 or 747 to King æthelbald of Mercia, in which Boniface describes how a single evil spirit (“malignus spiritus”) drove the king’s predecessor to a “madness clamoring with [multiple] demons” (“cum diabolis sermocinans”) (Dendle 90). Such coordinating (and often apposite) descriptors of demons fluctuate between a singular presence and a host of demons, and this manifestation occurs in Old English as well. Vercelli Homily 12 apposes the plural “helle gæstes” and “dioflum sylfum” (“evil spirits” and “devils themselves”) with the singular “dioful” (Dendle 91), and in the poem Juliana, the son or emissary of Satan is described as “wrohtes wyrhtan” and “fyrnsynna fruman” (“worker of evil” and “author of old sins,” lines 346 and 347), but this individual demon claims responsibility for endless evil and all of the crimes against humanity, including the original temptation in the Garden of Eden. In these examples and many others, demonic nature is a collective entity and one that fluctuates indiscriminately between a singular presence and a host of creatures. Demons also figure prominently in the Latin and Old English texts on the Anglo-Saxon saint Guthlac of Mercia, and I will write about him in the next blog post!

This plurality is also shown in the tenth-century Old English poem Christ and Satan, which centers on Christ’s triumph of Satan in the desert, while looking backwards towards the expulsion of Satan and the rebel angels from heaven, as well as forwards to Christ’s death, the harrowing of hell, and the resurrection. The early section of the poem includes a lot of “woe is me” sentiment by Satan and the demons, as they look back on their short existence in heaven and their current dire fate in the fires of hell, and the poet uses such sentiment to remind his reader to follow the righteous path and avoid such eternal punishment. The poem describes the demons in many colorful ways, including: “atole gastas, swarte and synfulle” (hideous spirits, black and full of sin (line 51)); “earme æglecan” (wretched monsters (74)); “blacan feond” (black fiend (195)); “godes andsacan” (God’s adversaries (279)); and “werige gastas, helle hæftas” (accursed spirits, prisoners of hell (628)). The poem also includes a further description of demonic classification, as one of the demons describes their nature: “Now this multitude must lie here according to its crimes; some to flutter aloft and fly above the ground. Fire envelopes each one, though he may be on high. He is never allowed to touch those blessed souls which seek upwards there from the earth; but I with my hands am allowed to snatch down to the depths the heathen chaff, God’s adversaries. Some are to roam about through the land of men and often stir up strife in the families of men throughout middle-earth” (254ff, all translations are from Bradley). In this poem the demons speak as a collective “we,” but also as a singular “I,” and they/ it are forever intertwined with Satan, but they/ it also seem to hate him for his overweening pride, telling him: “your appearance is hideous; we have all fared as wretchedly because of your lies. You told us a truth that the ordaining Lord of mankind was your son; now you have all the more torment” (53ff).*

Question 2: What connection or similarity exists between the demons (and specifically Satan) and other miserable exiled wanderers in Old English literature? In terms of the circumstances and reasons for exile, or the duration of the sentence, does a comparison between Christ & Satan and The Wanderer (for instance) reveal anything about Anglo-Saxon cultural and religious values?

Late Medieval Individual Demons

John Shinners’ textbook Medieval Popular Religion includes the chapter “Devils, Demons, and Spirits,” which describes a number of encounters with demons in rural Western Europe. In these stories and in texts like the fourteenth-century mystical vision Piers Plowman, we encounter individual demons with fabulous names and distinct personalities—Langland’s Gobelyn, Ragamoffyn, and Astarot are a few demons that immediately come to mind. Dante’s vision of hell in the Inferno includes the demon Alichino (the Allurer), who wields a hook and keeps the souls of the damned in boiling pitch, and he is assisted by Barbariccia (the Malicious), Draghignazzo (the Fell-dragon), and Malacoda (the Evil Tail). Demons also feature prominently in medieval drama, such as the buffoon like “stage demon” who appears in various works, including “Fall of Man” from the fifteenth-century York Mystery Plays, and Tutivillus, from the fifteenth-century morality play Mankind, who parodies monastic life. Also, one of my colleagues mentioned how Satan transgresses traditional dramatic boundaries by starting out in the audience in the York Plays, and this invasion is echoed and answered by Christ’s invasion of hell in the harrowing episode after his crucifixion.

The later medieval period also featured many religious and philosophical texts that classified demonic nature by describing the different types and characteristics of the demonic. Dyan Elliott’s Fallen Bodies: Pollution, Sexuality, and Demonology in the Middle Ages describes a number of these demonological texts, including Caesarius of Heisterbach’s thirteenth-century Dialogus Miraculorum, which describes demons as a collective, infighting, and chaotic group that is often referred to as “the devil.” Caesarius (among other authors) describes human susceptibility to demonic sexual harassment and nocturnal intercourse by the female succubus and the male incubus, and these demons could fashion their earthly bodies from wasted human seed. Thomas Aquinas writes on demonic nature in his thirteenth-century texts, including De Malo and De Trinitate, where he claims that demons could change sex (and shape) to acquire human seed from a man and deliver it to a woman to propagate monstrous offspring. The Visio of fourteenth-century peasant woman Ermine de Reims describes how she suffered through nightly visitations by demons in the forms of animals, people, angels, and even God, and these demons often engaged in lascivious sexual acts. (During our discussion we also talked about related manifestations of the demonic in medieval visionary literature, such as the writings by and about women like Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe.) The late fifteenth and early sixteenth-century German churchman Johannes Trithemius furthers demonic classification in his writing—the Mystical Chronology divides demons by their elemental nature into Igneum (fiery demons), Aereum (air demons who cause overcast skies, thunder, and lightning), land-demons (who inhabit the woodlands and caves), and Aquaticum (water demons who topple ships and drown humans). Leander Petzoldt describes Trithemius’ demonology in the essay “The Universe of Demons and the World of the Middle Ages” in Ruth Petzoldt and Paul Newbauer’s Demons: Mediators between this world and the Other, which also describes the demonic spirits through which magicians could communicate over long distances in the Stenographia, including the water demon Hydriel, the air demon Icosiel, and Buriel the cave-dwelling light-shunner. (By the way, Jeffrey Cohen provides an insightful meditation on the demonic origins of Merlin in the writing of Geoffrey of Monmouth in his blog In the Middle.)

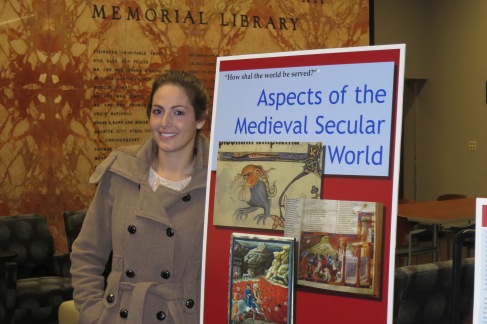

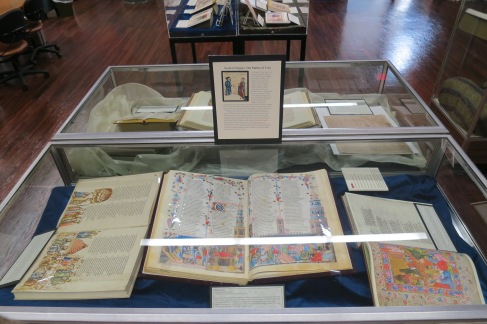

Finally, medieval manuscripts showed the evil and chaos of Satan and demons through their illuminations. In stark contrast to the bright, peaceful, and graceful depictions of angels, the demons of medieval manuscripts are often dark and shadowy creatures with scowling or lascivious expressions and contorted bodies, shaggy hair, horns, long pointed or hooked noses, gaping jaws, faces that combine human and animal elements, goat or bird legs, hooves or claws, tails, and bird- or dragon-like wings. The thirteenth-century De Brailes Psalter (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, MS 330) shows the demons being cast out of the orderliness of heaven and into the folio’s bottom half (image to the left), where they gain snarling and hideous demonic faces. The fifteenth-century Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur (Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Douce 134) features numerous images of Satan and his attendant demons, such as fol. 98r at the top of this post. This astonishing manuscript depicts numerous demons attending to Satan or torturing humans with pitchforks, and no two share the same monstrously animalistic facial and bodily features. The overall effect is a haunting tableau of beaks and horns, tails and wings, and the many faces of evil, all with snarling and sadistic grins that forever seek to tempt the innocent and torture the damned. In addition to these visualizations, demons are also pictured as more human-like creatures, albeit with deformed and barbaric features. Norbert H. Ott’s essay “Facts and Fictions: The Iconography of Demons in German Vernacular Manuscripts” in Petzoldt and Newbauer’s collection describes the demonic as “a manifestation of the different, the non-human, the sub-human, signifying a disordered and therefore threatening nature” (27). Because of this sub-human nature, demons were also equated with the cultural and geographic “Other” as defined by medieval Christian Europe, especially Jews, dark-skinned Ethiopians, and the fantastic monsters of travel literature.

Finally, medieval manuscripts showed the evil and chaos of Satan and demons through their illuminations. In stark contrast to the bright, peaceful, and graceful depictions of angels, the demons of medieval manuscripts are often dark and shadowy creatures with scowling or lascivious expressions and contorted bodies, shaggy hair, horns, long pointed or hooked noses, gaping jaws, faces that combine human and animal elements, goat or bird legs, hooves or claws, tails, and bird- or dragon-like wings. The thirteenth-century De Brailes Psalter (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, MS 330) shows the demons being cast out of the orderliness of heaven and into the folio’s bottom half (image to the left), where they gain snarling and hideous demonic faces. The fifteenth-century Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur (Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Douce 134) features numerous images of Satan and his attendant demons, such as fol. 98r at the top of this post. This astonishing manuscript depicts numerous demons attending to Satan or torturing humans with pitchforks, and no two share the same monstrously animalistic facial and bodily features. The overall effect is a haunting tableau of beaks and horns, tails and wings, and the many faces of evil, all with snarling and sadistic grins that forever seek to tempt the innocent and torture the damned. In addition to these visualizations, demons are also pictured as more human-like creatures, albeit with deformed and barbaric features. Norbert H. Ott’s essay “Facts and Fictions: The Iconography of Demons in German Vernacular Manuscripts” in Petzoldt and Newbauer’s collection describes the demonic as “a manifestation of the different, the non-human, the sub-human, signifying a disordered and therefore threatening nature” (27). Because of this sub-human nature, demons were also equated with the cultural and geographic “Other” as defined by medieval Christian Europe, especially Jews, dark-skinned Ethiopians, and the fantastic monsters of travel literature.

Question 3: Where does this impulse to understand and categorize demonic nature come from, and what connection do these texts have to medieval concepts of science and medicine? What changes in religious thought, philosophy, or even English (French, German, etc.) culture lead to such a seemingly different and more complex understanding of demons and demonic nature?

Question 4: How does medieval demonology connect with or progress towards the early modern witch-hunting craze and a broader definition of the term “demon”?

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

*There are also a lot of fascinating spatial dimensions to Christ & Satan, and my fellow Woode-walkers know that I am intensely interested in spaces, places, and landscapes. These insights will have to wait for a future post, however, where I will examine how the demons are exiled from the “settled abode” and “wine-hall of the doughty” of heaven and forced to walk to earth as exiles, but also, paradoxically, remain trapped in the dark (but full of blazing fire) and confining (but also cavernous) abode of hell. There is something really interesting about heaven and hell as contrasting (or perhaps negatively related) homes or halls, each of which is heavily fortified in its own right, but such thoughts will have to remain on the back burner for now.

Bibliography

Anderson, M. D. “The Stage Demon.” Drama and Imagery in English Medieval Churches. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1963: 171- 180. Print.

Blumenfeld-Kosinski, Renate. “The Strange Case of Ermine de Reims (c. 1347- 1396): A Medieval Woman between Demons and Saints.” Speculum 85.2 (2010): 321-56. Print.

Boureau, Alain. Satan the Heretic: The Birth of Demonology in the Medieval West. Chicago: U Chicago P, 2006. Print.

Bradley, S. A. J., Ed. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: David Campbell, 1982. Print.

Brann, Noel L. Trithemius and Magical Theology: A Chapter in the Controversy over Occult Studies in Early Modern Europe. Albany: State U of New York P, 1999. Print.

Dendle, Peter. Satan Unbound: The Devil in Old English Narrative Literature. Toronto: U Toronto Press, 2001. Print.

Elliot, Dyan. Fallen Bodies: Pollution, Sexuality, and Demonology in the Middle Ages. Philadelphia: U Pennsylvania P, 1999. Print.

Ott, Norbert H. “Facts and Fictions: The Iconography of Demons in German Vernacular Manuscripts.” Demons: Mediators between this World and the Other: Essays on Demonic Beings from the Middle Ages to the Present. Ed. Ruth Petzoldt and Paul Neubauer Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1998. Print.

Roberts, Gareth. “The Bodies of Demons.” The Body in Late medieval and Early Modern Culture. Darryll Grantley and Nina Taunton. Aldershot: Ashgae, 2000: 131- 142. Print.

Russell, Jeffrey Burton. Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages. Ithaca: Cornell U P, 1984. Print.

Shinners, John. Ed. “Devils, Demons, and Spirits.” Medieval Popular Religion, 1000- 1500: A Reader. 2nd Edition. Toronto: Broadview Press, 2007. 229- 280. Print.

Strickland, Debra Higgs. Saracens, Demons, & Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2003. Print.

Read Full Post »

You must be logged in to post a comment.